Filed under: Uncategorized

After a very lengthy hiatus, I have resumed producing content – but now about a range of subjects in Science and History broadly (Paleontology still features!). You can follow me at www.scribblopedia.com

Hope to see you there!

NOTE: This post is about birds that lost the ability to fly and evolved to occupy ecological niches typically associated with big mammals. In the sections that follow, we will study birds as large, terrestrial grazers (moas), as sea-going, flipper-possessing hunters of fish and krill (penguins) and as fleet-footed, land predators (phorusrhachids).

The Moa

The first voyagers touched land on the coast of New Zealand some time before 1300 AD. The coming of man signaled the beginning of a devastating mammalian assault on the island’s ecosystem. This isolated land-mass in the southern Pacific, where all land mammals but bats had been extinct for millions of years, was suddenly overrun with human, canine and rodent invaders from Polynesia. A wave of deforestation and extinction ensued.

Richard Owen with the skeleton of a Moa

New Zealand’s earliest colonists belonged to a great seafaring culture with an impressive history of settling remote island chains. As they explored the land, they encountered massive flightless birds and the largest species of eagle in the world. Descriptions of these spectacular creatures survived in oral legends, centuries after they had been extirpated by hunting and habitat change.

In the near complete absence of mammals, birds dominated the vertebrate fauna of New Zealand prior to human contact. Instead of ungulate browsers and grazers, there were different species of moa. Instead of small mammals foraging in the leaf-litter at night, there were nocturnal kiwis. The island’s largest predator was a raptor with a wingspan of three meters, the Haast’s eagle. In short, it was home to a truly astonishing range of avian species, from penguins to parrots. In this section, I will focus on the biology of the Moa – the most famous of New Zealand’s extinct birds.

New Zealand was once home to 9 species of moa. These birds were ratites – flightless relatives of ostriches, emus and cassowaries. The defining characteristic of this group is the absence of a keel on the breastbone which, in flighted birds, serves as an attachment surface for powerful wing muscles. Ratites (and tinamous) branched off relatively early in the evolution of modern avians (Neornithes). Much controversy has surrounded the timing and nature of their divergence from the rest of bird-kind: did ratites evolve in the cretaceous, prior to the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, or after?

During the late cretaceous, the supercontinent of Gondwana (itself the southern fragment of an earlier, larger and more famous supercontinent: Pangea) split into a number of smaller continents and islands that today account for almost all of the landmass in the southern hemisphere (namely, Africa, South America, Antarctica and Australia)*. Tellingly, all modern ratites live in these southern bits of gondwana: ostriches in Africa, rheas and cassowaries in South America, emus in Australia and kiwis in New Zealand. This distribution suggests that the most recent – and presumably flightless – ratite common ancestor arose in Gondwana during the Cretaceous period. As the continents drifted apart, descendant ratite lineages “rode” the crustal fragments to their present locations, evolving in geographic isolation. However, more recent DNA evidence complicates and challenges this picture. No published molecular evolutionary tree describing the branching events between different ratite species conforms exactly to what we would expect based simply on the order of separation of the Gondwanan continents. Furthermore, an important paper (Harshman et al. 2008) nests tinamous, which are weak-flying birds from South and Central America, within the ratite clade, and identifies ostriches as the most deeply diverging ratite group. At first blush, that might appear to indicate that tinamous are ratites that somehow re-evolved flight. However, no avian group is yet known to have lost and then regained the ability to fly. A number of such phylogenetic studies have raised an intriguing possibility: perhaps the last shared ancestor of all living ratites was a bird fully capable of flight. This would imply that flightlessness evolved more than once among ratites – and that the keel-less breastbones and non-functonal wings of ostriches and emus may actually be an astonishing example of parallel evolution. The global distribution of ratites may be best explained by volant ancestors dispersing across bodies of water and by independent losses of flight in different lineages.

Polynesians hunting a giant moa. Painting by Heinrich Harder.

The moa head was small relative to body size. They had long necks and stout legs. Moas were unique among flightless birds in lacking even vestigial wings. At a height of 3.6 meters, the Giant Moa towers over the biggest of its extant relatives, the ostrich. The only birds that are known to have surpassed the largest moas in weight were the elephantbirds of Madagascar – another group of giant, island ratites that went extinct within the last millennium. The smallest species of moa approximated the size of a turkey.

Moa were herbivores that lived in or on the edges of forests, feeding on twigs and branches from low trees and shrubs. Like all other birds, they possessed a gizzard – a stomach chamber with thick, muscular walls containing stones that the bird swallowed to aid in digestion. Driven by powerful muscular contractions, these stones helped grind down ingested plant material. Gizzard stones are the functional equivalent of mammalian teeth. Moa did not live in a world free of natural predators. In the 1870s, half a century after the first moa bones were described by European scientists, a number of bones were discovered at a moa-excavation site that seemed to belong to giant bird of prey. This bird, called the Haast’s eagle, had a wingspan that exceeded that of any living raptor or vulture. It is thought to have preyed on moa. Watching one of these eagles swoop down on and dispatch a moa several times its size would have been a sight indeed!

The Haast’s eagle preyed on moa. Artwork by John Megahan.

Within a century of polynesian arrival, the Moa was hunted to extinction. The decimation of New Zealand’s forests also played a role. By the time the first Europeans set foot on the island, the moa was only a distant mythical-cultural memory to the Maori.

Penguins

The six living genera of penguins (and their various extinct relatives) together constitute the avian order Sphenisciformes. They are undoubtedly the most aquatically-adapted of all birds. Studies have revealed the body-form of a penguin to be among the most hydrodynamic shapes in the animal kingdom. Its wings have evolved into stiffened flippers that are optimized for generating thrust underwater. Their webbed feet, which serve as the primary source of propulsion in many other diving sea-birds, are used for steering rather than paddling when underwater. It has densely-arranged, short feathers that serve to insulate and make the animal waterproof. It has dense bones that allow it to resist buoyancy and dive deep in pursuit of prey. Emperor penguins, for example, are capable of diving down to over 1,800 feet. Many species forage for krill, squid and fish hundreds of kilometers away from the location of their home colonies. While penguins are typically imagined to be remote denizens of frigid Antarctic coasts, they are actually found throughout the Southern Hemisphere. Consider that Galapagos penguins cross the equator on a regular basis!

The oldest known Sphenisciforme fossils date to the Paleocene, around 60 million years ago, not long after the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs. These bones belong to the species Waimanu manneringi, a long-billed, flightless water-bird with forelimbs that show some signs of adaptation toward wing-propelled swimming. It probably used its feet to actively propel itself, rather than employing them simply as a rudder like modern penguins. Its skeleton presents an early stage in the anatomical evolution of penguins.

Interestingly, a number of gigantic penguin species have been discovered from the Eocene (56-33 mya) and Oligocene (33-23 mya) periods. Like ratites, the Sphenisciformes were able to experiment with larger body-sizes once they abandoned flight. Anthropornis, the tallest of them, stood at about 5 feet and 7 inches. Its wings were not as straight as those of modern penguins. Icadyptes, another one of these fossil giants, possessed an elongate, spear-like beak for skewering fish and may have been a strong diver. One interesting, if largely speculative, hypothesis posits that rising competition for food stocks and predation pressure imposed by the emergence of new lineages of whales and pinnipeds (i.e. seals) during the Oligocene drove giant penguins to extinction. By a similar token, perhaps the earlier extinction of large marine reptile groups after the cretaceous period opened up fresh new watery niches for early penguins to exploit. While the Sphenisciformes as a whole are certainly a very ancient group, all living penguin taxa trace their descent to an ancestor that lived only 10-11 million years ago.

In an interesting evolutionary parallel, auks in the northern hemisphere independently evolved wing-propelled swimming, an upright posture and black-and-white colors. Living auks are generally inefficient fliers – having traded in much of their flying ability for swimming prowess – but none of them are flightless. The great auk is an extinct member of the group that was flightless and disappeared only 150 years ago. Curiously, the word “penguin” was originally applied to this species of auk, prior to the discovery of what know today as penguins by western explorers.

A stuffed great auk

The Phorusrachids

South America was an island continent for nearly all of the Cenozoic era (i.e. the last 65 million years). While elephants, horses, camels, cats, dogs and bears were evolving in and dispersing throughout the Old world and North America, South America’s mammal fauna remained isolated and evolved in its own distinct fashion. The land mass was once home to elephant-sized sloths, the marsupial equivalents of ‘saber-toothed’ cats, and many strange and unique ungulates. These fascinating creatures will be the subject of a future post. South America was also home to a clade of large, flightless birds with a predilection for meat- the Phorusrhacids. Their closest living relatives are two species of seriema – long-legged, mostly-terrestrial, carnivorous birds native to the same continent.

Titanis walleri, a large North American Phorusrhacid, artwork by Dmitry Bogdanov

Unlike some other candidate “Terror birds” from the fossil record, like the Mihirungs of Australia or the Gastornithiformes, there has been relatively little debate about whether or not Phorusrhacids were predators. They had large skulls with tall, laterally-compressed and strongly- hooked beaks. The neck was not built to withstand side-to-side stresses (so these birds could not snag and then violently shake their prey), but could mete out powerful downward strikes. The biggest known Phorusrhacids were around 3 meters tall. Large phorusrhacids are often described as being agile pursuit hunters. Their legs might have also been employed in kicking prey to death, a tactic used to great effect by the secretary bird, a living terrestrial bird of prey in Africa.

South America’s long isolation ended when the Isthmus of Panama formed 4.5 million years ago, connecting the continent to North America. This inaugurated a fascinating period of inter-continental animal migrations that permanently changed the faunal composition of South America. Northern species were generally more successful in invading the south than vice-versa. The phorusrhacids did manage to spread north of the isthmus and the remains of one impressive species, Titanis walleri, have been recovered from Texas and Florida. They went extinct not long after this event (perhaps succumbing to competition from a host of new carnivorous mammalian rivals) about 2 million years ago, well before humans entered the New World.

References

Phillips, Matthew J., et al. “Tinamous and moa flock together: mitochondrial genome sequence analysis reveals independent losses of flight among ratites.”Systematic biology 59.1 (2010): 90-107.

Smith, Jordan V., Edward L. Braun, and Rebecca T. Kimball. “Ratite nonmonophyly: independent evidence from 40 novel loci.” Systematic biology62.1 (2013): 35-49.

Phillips, Matthew J., et al. “Tinamous and moa flock together: mitochondrial genome sequence analysis reveals independent losses of flight among ratites.”Systematic biology 59.1 (2010): 90-107.

Worthy, Trevor H., and Richard N. Holdaway. The lost world of the moa: prehistoric life of New Zealand. Indiana University Press, 2002.

Dyke, Gareth, and Gary Kaiser, eds. Living dinosaurs: the evolutionary history of modern birds. John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Degrange, Federico J., et al. “Mechanical analysis of feeding behavior in the extinct “terror bird” Andalgalornis steulleti (Gruiformes: Phorusrhacidae).” PloS one 5.8 (2010): e11856.

*India and Arabia are portions of Gondwana that have moved entirely into the northern hemisphere.

This post is the third installment in a multi-part series on the evolution of mammal-like reptiles.

Time has turned it to rock, but despite the passage of so many millions of years, the head of a gorgonopsid still retains an aura of unspeakable ferocity.

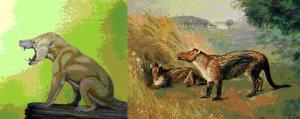

Gorgonopsia is a suborder of predaceous therapsids (“mammal-like reptiles”) that arose during the Middle Permian. For much of their early evolutionary history, gorgonopsians were rare, modest-sized carnivores, eclipsed in numbers and ecological relevance by thick-skulled, meat-eating Dinocephalians. The (rather unexplained) demise of the Dinocephalians at the end of the Middle Permian threw open new predatory niches for these “gorgon-faced” hunters to exploit.

The most striking feature of the gorgonopsid skull is the presence of two enlarged canines – reminiscent of the dagger-like fangs of sabre-toothed cats from the far more recent Pleistocene epoch – that hang menacingly from the upper jaw. The lower canines were also massive -often only a third shorter than their upper counterparts. To sufficiently clear the canines before delivering a lethal bite, these animals must have been capable of drawing back their lower jaws far enough to produce gape angles in excess of 90 degrees. Kemp’s (1969) functional analysis suggests that Gorgonopsid jaws were capable of performing two kinds of bites: (1) a killing bite in which the animal would use its fearsome canines as stabbing devices, piercing through hide and flesh to disable its prey. The front end of the lower jaw bears a large, massy “chin” that may have served as the mechanical equivalent of a war-club, packing an extra kinetic “punch” when the jaws were drawn shut. (2) a more surgical type of bite in which the incisors interlocked when the jaws were closed, allowing the animal to slice out a jagged edged hunk of flesh from a carcass. The transtion from biting mechanism (1) to (2) was made possible by the movement of the lower jaw to a more forwardly position so that the serrated incisors could intermesh.

The large size of the snout indicates that smell was key to the hunting behavior of these ancient predators.

Arctops watsonii, a South African Gorgonopsid Image Credit: Богданов

Compared to pelycosaurs like Dimetrodon, Gorgonopsids have rather gracile post-cranial skeletons with limbs that are longer and more vertically oriented. There was probably less lateral swaying of the trunk during locomotion and the back was kept straighter. The tail was smaller. The body was held well clear off the ground and some skeletal reconstructions of Gorgonopsids even evoke a sense of wolf-like nimbleness. According to some workers, the nature of the articulation between the femur and the acetabular socket of the pelvis suggests that the gorgonopsid hindlimb was capable of switching between a primitive splayed posture and a more erect mammalian stance (similar to the “high walk” of a crocodile). The precise character of limb suspension in Gorgonopsids – which probably lay somewhere in the gray-zone between ‘sprawling’ and ‘fully erect’ – is still debated. The hind-limbs (which accounted for the bulk of the animal’s speed and propulsive power) were more upright than the fore-limbs.

While body form did not vary considerably among different gorgonopsid genera, there was certainly a range in size . The smallest known gorgonopsids are comparable in body dimensions to modern day canids. The largest gorgonopsids (members of the genus Inostrancevia, for example) measured around 3.5 meters from nose-tip to tail-end, making them longer than any living land carnivore. These late Permian super-predators were well-adapted for hunting huge, stocky, slow-moving, plant-eating dicynodonts and paraeiasaurs. In some ways, this mode of life was replicated in a much later era by saber-toothed cats that preyed heavily on herbivorous megafauna.

Large gorgonopsids hunted big game. In this reconstruction, Inostrancevia kills a juvenile pareiasaur. Image credit: Dmitry Bogdanov

It is worth listing some of the other important features gorgonopsids bear in relation to the pelycosaur-to-mammal transition (the ‘advanced’ traits are italicised and the ‘primitive’ pelycosaur-ish traits are indicated in normal font) – (1) a secondary palate is absent, (2) the dentary of the lower jaw is expanded, (3) the stapes is reduced, (4) cervical and lumbar ribs are present, (5) they display the same advanced bone histology seen in Dinocephalians, (6) no definite statements on the presence or absence of body hair in gorgonopsids can be made. There is, however, a limited amount of evidence indicating that their snouts may have borne vibrissae or whiskers, (7) the relative size and shape of the brain had not changed significantly from the pelycosaur condition.

The gorgonopsids were wiped out by the end Permian extinction event. After their disappearance, new non-therapsid animals would come to take on the mantle of terrestrial super-predator – among them, Raiusuchians and Theropod dinosaurs.

In the next post in this series, we’ll spend some time on two more Therapsid groups: the Dicynodonts and the Therocephalians.

Sources:

1. Kemp, Thomas Stainforth. “On the functional morphology of the gorgonopsid skull.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences (1969): 1-83.

2. Kemp, Thomas Stainforth. The origin and evolution of mammals. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

3. Kemp, Thomas Stainforth, and T. S. Kemp. Mammal-like reptiles and the origin of mammals. London: Academic Press, 1982.

4. Chinsamy-Turan, Anusuya, ed. Forerunners of Mammals: Radiation• Histology• Biology. Indiana University Press, 2011.

6. Van Valkenburgh, B. L. A. I. R. E., and I. Jenkins. “Evolutionary patterns in the history of Permo-Triassic and Cenozoic synapsid predators.” Paleontological Society Papers 8 (2002): 267-288.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Generations of fossil hunters have visited the arid fields of the Karoo basin in South Africa in search of ancient life. The rock-layers of the Karoo constitute an invaluable storehouse of information on the evolutionary history of the Therapsids. They have, over the course of a century, yielded up many strange and forgotten Permian beasts – mineralized relics from a time when the Karoo was a far greener place.

The Karoo Basin in South Africa has provided great insights into the story of Therapsid evolution during the Permian period

What are Dinocephalians and what do they have to do with Therapsid evolution?

The Dinocephalians represent the first significant wave of Therapsid diversification. They were a group of medium-to-large sized herbivores and carnivores that enjoyed global distribution during the Middle Permian. Paleontologists have identified a few features that seem to unite the group:

1) The upper and lower incisors interlocked when the jaws were drawn shut. The lower incisors had surfaces on the tongue-ward side called ‘heels’ that met with the upper incisors to form food-crushing platforms.

2) The nose projects ventrally in many forms, giving the face a markedly downturned appearance

3) The jaw is shortened and the jaw-joint is is more anteriorly situated

4) Significant thickening of the skull bones (“pachytosis”) is a commonplace feature – hence the name “Dinocephalia”, which means “terrible heads”.

5) The temporal fenestra is longer along the dorso-ventral axis than the antero-posterior axis.

Large herbivorous dinocephalians like Tapinocephalus and Moschops attained weights and lengths comparable to modern oxen and rhinoceri (I seem to recall one author referring to Moschops – an awkward-looking and ponderous creature, judging from standard skeletal reconstructions – as “the Fat Albert of the Permian”). The post-cranial skeleton of Moschops is heavy-set, with several features that assisted in weight-bearing, including a massive shoulder girdle, arm bones with broad, flattened ends and short, stout vertebrae. The forelimbs probably assumed something of a sprawling posture, while the smaller hind-limbs were more erect. The frontal and parietal bones of the skull display an extraordinary degree of pachytosis, with thicknesses of upto 11.5 cm. The functional significance of the thickening of the skull roof in dinocephalians is unclear. The most popular theory is that the male members of these species used their skulls as rams and butted heads in dominance rituals.

Moschops, a herbivorous Dinocephalian. Image credit: Dmitry Bogdanov

Were Dinocephalians warm-blooded?

The temperature physiology of these animals is a point of uncertainty. Dinocephalians were apparently capable of living at high latitudes with highly seasonal weather regimes (their Pelycosaur forebears were, as far as we know, restricted to equatorial climes) and their bone-tissues display patterns of vascularization and growth similar to what is seen in mammalian bones. These are the arguments usually presented in favor of Dinocephalian warm-bloodedness. However, it must also be noted that the Dinocephalians lacked a number of key skeletal features often associated with endothermy in mammals. For example, they did not possess a secondary palate – an anatomical structure that separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity in mammals. The presence of this separation allows mammals to breathe continuously while feeding.

Plant-eating dinocephalians almost certainly found themselves, from time to time, in the predatory cross-hairs of carnivorous dinocephalians. The anteosaurs, for example, were a group of medium and large bodied meat-eating dinocephalians with high, narrow skulls, thickened skull roofs and large, robust canines. They were heirs to a set of ecological niches that, during the early Permian, would have been occupied by sphenacodontid pelycosaurs (including Dimetrodon). The largest known anteosaurs had skulls measuring over a meter in length.

A Russian Anteosaur, Titanophoneus. Image Credit: Mojcaj

Therapsids and Food-chains

Grasses carpet a hinterland plain. The grasses are gnawed down by great itinerant masses of wildebeest. The wildebeest are preyed upon by prides of lions. Food chains of this nature – in which energy flows from land-plant producers (eg. grass) to a class of abundant herbivorous primary consumers (eg. wildebeest) and, finally, to a relatively small population of carnivorous secondary consumers (lions) – are quite familiar to us. However, terrestrial ecosystems may not have always relied so heavily on a productive base of land-bound photosynthesizers. It has been suggested that, prior to the appearance of the Therapsids, land ecosystems were generally more dependent on aquatic productivity. This hypothesis is based on two observations: (1) the unusually high ratio of carnivorous pelycosaurs to herbivorous pelycosaurs in early Permian assemblages. An exclusively land-based food web would require a massive preponderance in numbers of herbivores over carnivores. (2) the abundance of fish-eating forms like Ophiacodon, that may have served as intermediate links in food chains that tied land to freshwater. The was an increase in the relative number of land-going vertebrate herbivores to carnivores after the rise of the Therapsids. The first large-bodied terrestrial plant-eaters were not Dinocephalians (both the Caseids and the Diadectids had played that part before during the early Permian; see my post on Pelycosaurs and on Amniotes), but Dinocephalian diversification (and Therapsid diversification in general) may have played a role in the creation of food-webs that were more plant-based and less fish-based.

The reign of the Dinocephalians was short lived – geologically speaking. They perished shortly after reaching the pinnacle of their taxonomic diversity around 263 million years ago, leaving no living descendants. But the Therapsid story was far from over. In the next few posts, we’ll discuss some of the Therapsid groups that ruled during the late Permian, starting with the Gorgonospids and Therocephalians.

Sources:

1. Kemp, Thomas Stainforth. The origin and evolution of mammals. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

2. Kemp, Thomas Stainforth, and T. S. Kemp. Mammal-like reptiles and the origin of mammals. London: Academic Press, 1982.

3. Chinsamy-Turan, Anusuya, ed. Forerunners of Mammals: Radiation• Histology• Biology. Indiana University Press, 2011.

4. MacLean, Paul D., Jan J. Roth, and E. Carol Roth. The ecology and biology of mammal-like reptiles. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1986.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Introduction to the Therapsids

2, 3, 3, 3, 3. That’s the number of bones in your thumb, index finger, middle finger, ring finger and little finger respectively. The same numbers apply to the phalangeal bones in your toes, starting with your big toe. This basic structural plan (common to most land mammals) has a very ancient pedigree – the therocephalia, a group of carnivorous “mammal-like reptiles” that walked the earth over 250 million years ago during the Permian period, had hands and feet constructed in just this fashion. Four out of the five digits on each extremity contained 3 bones while the remaining digit (corresponding to the thumb or big toe) contained only 2.

Many of the most unique and widely conserved features of mammalian anatomical design and physiology – including a bony secondary palate, a three-ossicle ear, endothermy, an erect limb-posture, and quite probably hair and lactation – originated among ancestral groups of “mammal-like reptiles” during the Permian and early Triassic periods.

Much of this series will be concerned with ‘bridging’ some of the ‘evolutionary distance’ that separates the pelycosaur Haptodus (left, by Nobu Tamura) from the early mammal Morganucodon (right, by Michael B. H.).

So how did the evolutionary process derive a class of highly active, fur-clad, milk-producing animals from ancestral forms that were so fundamentally reptile-like in appearance? This is the question that I shall attempt to answer in a series of posts over the course of this winter.

We discussed the biology and classification of some of the earliest “mammal like reptiles” in my post on Pelycosaurs. In this post, we shall begin to deal with their Permian heirs, the Therapsids. The first few installments of this series will deal with specific groups of mammal-like reptiles that lived during the Middle and Late Permian, while the remaining parts will deal with some of the long-term evolutionary ‘trends’ we can glean from the Therapsid fossil record.

What is a Therapsid?

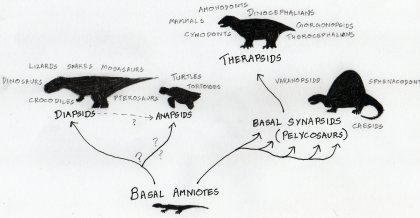

A very crude evolutionary tree. The word clouds around the ends of each of the branches represent different terms and animals associated with the taxonomic grouping.

Therapsida is a clade that owes its evolutionary origins to a pelycosaurian-grade ancestor and includes all of the most ‘advanced’ synapsids, including modern mammals. If that sentence is gibberish to you, perhaps reading the first few paragraphs of my post on pelycosaurs will help demystify things. To summarize:

– Birds, mammals and modern reptiles are amniotes by descent. The first amniotes were terrestrially-adapted animals that laid water-proof eggs on dry land.

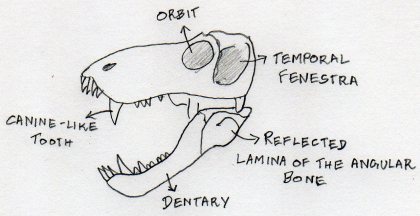

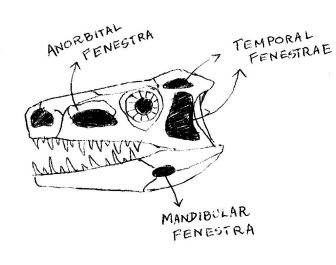

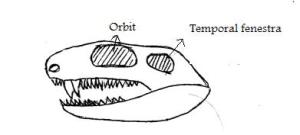

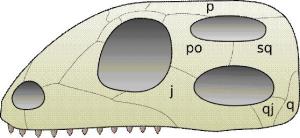

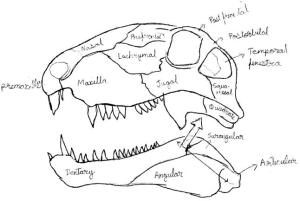

– Synapsida is a subgrouping of amniotes that includes modern mammals and their various extinct proto-mammal ancestors and relatives, but excludes birds and reptiles. Early synapsids can be distinguished from other groups of amniotes in the fossil record on the basis of a number of skeletal features, the most important of which is the presence of a single hole on each side of the skull behind the eye-orbit. These holes are called temporal fenestrae. By contrast, other early amniote skulls bear either no holes (anapsids), two holes (diapsid) or a single highly placed hole (euryapsid, similar to the synapsid condition, but differing in the location of the hole) behind each eye-orbit. The temporal fenestrae provide secure anchorage points for muscles associated with jaw function. Mammals are the only surviving synapsids.

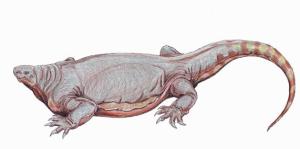

– ‘Pelycosaur‘ is a somewhat informal term applied to a range of basal/’primitive’ non-mammalian synapsids.

What differentiates early Therapsids from pelycosaurs?

The most important differences lie in the anatomy of the skull.

Therapsids have larger temporal fenestrae than pelycosaurs.

An enlarged canine-like tooth is present on the lower and upper jaws of Therapsids, clearly demarcating the boundary between a set of incisor-like teeth in front and a set of post-canine teeth behind. Heterodonty – or the presence of morphologically distinct sets of teeth in the jaws (e.g. incisors, canines, molars, premolars) – is one of the signature features of mammalhood. Most bony fish, amphibians and modern reptiles have ‘homodont’ teeth that are essentially morphologically identical.

The back of the skull in Therapsids is also more vertical and the jaw-joint is more anteriorly placed than in pelycosaurs.

The mammalian jaw consists of a single bone – the dentary. Earlier Therapsids had jaws constructed from a number of bones in addition to the dentary, including the angular bone (refer to diagram). One diagnostic feature of the therapsid jaw is the presence of a wide leaf of bone called the “reflected lamina” that protrudes from the angular. The reflected lamina may have played some part in hearing. We will discuss the evolution of the mammalian auditory system in a future post in this series.

The post cranial skeletons of early Therapsids show signs of improved locomotory ability. They appear to have traded in the permanent sprawling posture of their pelycosaur ancestors for a more erect gait and developed shoulder and hip joints that permitted a greater range of limb movements.

Most of the traits listed above were present in some incipient form in one group of Pelycosaurs in particular- the Sphenocodontidae. This group includes the famous sail-backed Dimetrodon. The Sphenocodontids are nearly universally posited as the closest relatives of the Therapsids.

Up next, the Dinocephalia.

Sources:

1. Kemp, Thomas Stainforth. The origin and evolution of mammals. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

2. Kemp, Thomas Stainforth, and T. S. Kemp. Mammal-like reptiles and the origin of mammals. London: Academic Press, 1982.

3. Chinsamy-Turan, Anusuya, ed. Forerunners of Mammals: Radiation• Histology• Biology. Indiana University Press, 2011.

4. MacLean, Paul D., Jan J. Roth, and E. Carol Roth. The ecology and biology of mammal-like reptiles. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1986.

Much of Siberia is sheathed in sub-artic grasslands, conifer forests and peat bogs today, but 250 million years ago it was the site of a volcanic episode of Armageddon-like proportions- great fissures developed in the earth’s crust and, over the course of a few million years, belched out one to four million cubic kilometers of blazing-hot basaltic lava. This eruptive event, among the largest in earth history, is thought to have triggered the Permian extinction.

The end Permian extinction, which eradicated over 90% of our planet’s plant and animal diversity within a relatively brief stratigraphic time window, was an extermination event of truly unimaginable magnitude. It has been referred to as “the Great Dying”, “The Mother of All Mass Extinctions” and “Life’s Greatest Challenge”. These apocalyptic titles are not without warrant and it can safely be said that the Permian-Triassic mass extinction represents the worst biotic crisis to hit the earth in the last 550 million years.

What was life like during the Permian?

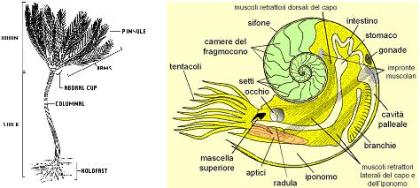

Complex ecosystems flourished both on land and under water during the Permian period. Mighty reefs, constructed from the hard limestone skeletons of ancient sponges, corals and bryozoans, rose up in the shallow tropical waters that covered much of West Texas, New Mexico and Northern Mexico. Huge numbers of fixed, rather plant-like echinoderms called crinoids or “sea lillies” thrived in and around the reef-forest. The Permian reef waters were home to a bewildering host of free-swimming, creeping and sedentary creatures: shell-bearing, jet-propelled cephalopods called Ammonites bustled about alongside throngs of fish and free-swimming arthropods; Snail-like animals, shelled bivalves, sea-urchins and starfish made a less mobile living amidst the thickets of coral

Primitive therapsids, the remote forerunners of modern-day mammals, were the dominant vertebrates on land at this time – ranging from huge sabre-toothed Gorgonopsids to beaked, plant-eating dicynodonts to terrier sized Therocephalians. The reptiles from this period include giant, stout-bodied herbivorous pareiasaurs and lizard-like millerettids. The Permian period saw the development of terrestrial food webs of unprecedented complexity. Keep in mind, in all of this, that the Permian began and ended well before the first dinosaurs evolved. I hope my readers will forgive the stark brevity of my descriptions here, for I intend to cover many of the faunal groups listed above in significant detail in future posts.

What changed at the end of the permian?

For starters, the vast reefs – burgeoning with all manner of marine life for millions of years – vanished at the end of the Permian. The end Permian event is followed by a 7 to 8million year long “reef gap” in the fossil record. The two dominant forms of coral at the time – the tabulate and rugose corals – were wiped out entirely by the event (stony corals are the primary reef builders in modern-day oceans).

Bivalves and Brachiopods are shelled marine animals with an evolutionary history that spans over 500 million years. They suffered heavy losses during the end Permian extinction, but managed to survive, recover and thrive into the present day. Mussels and clams are examples of bivalves – their soft bodies are enclosed in a pair of similar-looking shells called “valves” that are joined by a ligamentous hinge. Brachiopods, informally known as “lampshells”, bear two shells of unequal size and are similar in appearance to early Roman oil lamps. Some of the external differences between the two groups can be discerned in the image below. Bivalves are mollusks while the brachiopods constitute a phylum unto themselves – the rather astonishing phylogenetic implication of this statement is that Bivalves are actually more closely related to snails and squid than they are to the much more similar-looking brachiopods. Brachiopods were more abundant and diverse than Bivalves in the seas of the late Permian, but the situation was reversed permanently after the extinction event: the number of currently-existing Bivalve genera exceeds the number of living Brachiopod genera by a factor of nearly 10. Many reasons have been cited for the apparent competitive triumph of Bivalves over Brachiopods, including the greater range of habitats and niches that Bivalves are capable of successfully occupying and the generally higher metabolic rates they display. In all likelihood however, despite their external morphological similarities, the two groups may fill niches so radically different that direct competition between them was never an issue. They may have been, as two workers so keenly put it, “ships that passed in the night”.

The line of symmetry in a Brachiopod lies between the two sides of a single valve. The line of symmetry in Bivalves lies between the two valves.

Ammonites – tentacled free-swimming mollusks with coiled shells – were hard hit by the event, with 97% of known genera going extinct. But, like the Bivalves, they managed to recover and flourish in the following “Age of Reptiles”. They were ultimately done in by the K-T extinction event over 180 million years later.

Fixed, plant-like echinoderms (like sea-lilies and blastoids) accumulated in such numbers during the Permian that they essentially formed forests that carpeted the sea floor. These sessile animals were decimated by the Permian extinction and the “echinoderm forests” they formed were never reconstructed in any succeeding geologic period.

The holocaust was not restricted to large multicellular organisms: single celled planktonic organisms like radiolarians and foraminiferans took a severe beating as well. Radiolarians are microscopic floating creatures that construct elaborate skeletons of silica. When they expire, their skeletons sink and accumulate on the sea floor. Oozy accretions of radiolarian skeletons are transformed by a process of compaction and hardening, over a time span of millions of years, into chert, a fine-grained silica rich rock. There is a conspicuous absence of radiolarian cherts in the fossil record for an 8 million year period following the end-Permian event, indicating some kind of catastrophic radiolarian die-off.

So, in summary, from mollusks to oceanic microbiota, the Permian extinction wreaked havoc on marine life of all sizes and shapes.

On land, the situation was similarly grim. Huge numbers of plant and insect taxa fell. Roughly 2/3rds of all terrestrial vertebrate families vanished. Among the most incredible aspects of the end Permian saga on land, was the post-disaster ascendancy of a humble herbivore called Lystrosaurus to a level of global ecological predominance that has never been achieved by any other individual vertebrate genus (or family, really) in all of earth history. Lystrosaurus was a pig-sized therapsid – a scaly ancient relative of modern-day mammals. It was a beaked herbivore with two tusk-like canines and short, stout semi-sprawling limbs. Given the apparent paucity of big predators (and major herbivorous competitors, for that matter) in the post-Permian landscape, Lystrosaurus enjoyed free rein to multiply and diversify on an astonishing scale. Lystrosaurus remains make up over 95% of many vertebrate assemblages from the early Triassic (the period following the Permian). “In South Africa” natural historian Michael J Benton writes, “paleontologists cry with frustration when they find another Lystrosaurus skull”. Puzzlingly, however, it has no obvious features that mark it out as an animal built to survive extreme environmental conditions. Their possibly semi-aquatic mode of life, their much vaunted lack of ecological specialization and pure luck have all been put forward as possible explanations for their spectacular, albeit short lived, success.

Lystrosaurus

What caused the Permian extinction? Was it the result of a meteorite impact?

The causal mechanisms that drove so many varied forms to extinction have been speculated over for decades – historically, a wide range of phenomena have been called upon to account for the devastation, from trace element poisoning in the world’s oceans to elevated levels of cosmic radiation.

A cataclysmic meteorite impact – like the one that brought the reign of the Dinosaurs to an ignominious conclusion – would have left behind a signature of iridium and shocked quartz in the rock layers. Iridium is practically non-existent in the earth’s crust (less than 0.001 parts per million) but relatively common in meteorites. Significant quantities of it are found in the clays of the ‘Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary’ – the point in the fossil record beyond which the dinosaurs disappear. This iridium is thought to be of meteoritic origin. Quartz grains with clear signs of deformation by hypervelocity shock are also found at the boundary – the products of a violent collision. These and other pieces of evidence allow us to say, with some certitude, that the non-avian dinosaurs were done in by a space rock. Does the evidence stack up in strong favor of a meteorite impact at the Permian-Triassic boundary? In a word, no.

The evidence for a late Permian impact event is limited and hotly contested. For example, cage-shaped carbon molecules called fullerenes containing noble gases (argon and helium) with isotopic ratios that reflect an extraterrestrial origin were discovered at the Permian-Triassic boundary by a group of University of Washington researchers in 2001 – but their results were not successfully replicated when another team from Caltech analysed PT-boundary material from the same test areas. Published evidence of unusually high iridium levels and shocked quartz from an impact event at the PT boundary has been met with considerable skepticism from many in the scientific community.

The most popular extinction model points to an episode of intense volcanism, 250 million years ago in what is now Siberia, as the likely triggering mechanism. The Siberian traps – a large expanse of volcanic rock in Asian Russia stretching across 2 million square kilometers – were formed by this eruptive event. The eruptive style is worth comment: instead of viscous lava pouring out of classically conical volcanoes, one must imagine highly fluid lava issuing from huge fractures in the earths crust and flowing out over thousands of kilometers. Successive lava flows built up an immense layered plateau of basalt (basalt is essentially solidified lava). The threat that this event posed to life did not lie so much in the incessant outpouring of hot, fast-moving lava (which surely annihilated life within a regional radius) as in the outgassing of prodigious quantities of carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide.

There is good evidence to show that global temperatures rose considerably at the end of the Permian – and elevated atmospheric levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane most likely accounts for this change. The release of carbon dioxide by the Siberian traps event could have driven global temperatures up enough for another serious greenhouse gas source to come into play: gas hydrates.

Gas hydrates are crystalline solids in which gases are locked up in “cages” made of hydrogen-bonded water molecules. Carbon dioxide and methane containing gas hydrates may be found at great depths in sediments around the rims of continents and in permafrost. It is thought that gas hydrates today contain trillions of tonnes of stored carbon, much more carbon than can be found in the combined fossil fuel reserves of all of the nations on earth. The mass melting of frozen gas hydrates would have injected tremendous amounts of methane and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

The high temperatures would have also decreased the solubility of oxygen in water, leaving the world’s oceans relatively oxygen depleted. Anoxia – or oxygen deficiency – might have been the axe by which the Permian extinction cut down so many diverse families of marine life, particularly those reliant on the construction of calcium carbonate shells. Several lines of evidence point to widespread anoxia in the seas of that time – the presence of black mudstone, for example, in the layers that follow the PT boundary is a telltale sign of low oxygen concentrations. Anoxic conditions permitted the rapid proliferation of oxygen-hating sulfate-reducing bacteria that, in the presence of light, produce hydrogen sulfide – a gas that is toxic to most life forms and harmful to the ozone layer to boot.

Carbon dioxide is heavier than air and, even above water, can drive down oxygen levels by a process of simple displacement. Carbon dioxide is poisonous in high enough concentrations.

Sulfur dioxide, another major gaseous product of volcanic activity, is a precursor to acid rain. Acid rain would have wreaked havoc on terrestrial plant and animal life and introduced cocktails of acids into enclosed bodies of water. The sulfate aerosols that result from the interaction of sulphur dioxide with the earth’s atmosphere are actually capable of reflecting and scattering light from the sun. They may have induced a brief initial period of global cooling before the pronounced warming trend set in.

Hydrogen sulfide emissions, the spread of toxic ash, global warming, wild fires, acid rain, planet-wide anoxia and a weakening ozone layer are all phenomena that have been implicated, with good reason, in the Great Dying of the end Permian. There can be no doubt that this was an apocalypse, but it was not a simple apocalypse. It involved a complicated chain of events and employed multiple agents of death.

Sources:

1. Kemp, Thomas Stainforth. The origin and evolution of mammals. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

2. Donovan, Stephen K., and S. K. Donovan, eds. Mass extinctions: processes and evidence. London: Belhaven Press, 1989.

3. Ward, Peter D. Under a green sky: global warming, the mass extinctions of the past, and what they can tell us about our future. HarperCollins, 2007.

4. Benton, Michael J., and M. J. Benton. When life nearly died: the greatest mass extinction of all time. Vol. 5. London: Thames & Hudson, 2003.

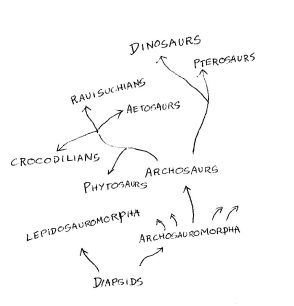

Filed under: Uncategorized

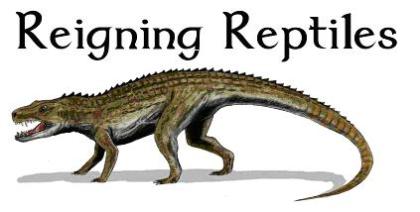

Many great dynasties of reptiles rose and fell during the early phases of the Mesozoic Era (a hefty block of geological time, sometimes called the “Age of Reptiles”, that lasted from 250 to 65 million years ago). The beaked rynchosaurs, the agile, erect-walking, predatory rauisuchians, the crocodile-like phytosaurs and armored aetosaurs all had their heydays within the first 50 million years of the Mesozoic.

The names of these lineages – successful though they were – are probably only familiar to professionals and die-hard enthusiasts. The same cannot be said of the ever-popular Dinosauria, whose first (relatively unassuming) representatives also appeared on the scene during this early-Mesozoic time interval, around 230 million years ago. The Dinosaur clade has attained tremendous public notoriety for its evolutionary experiments in large body-size, defensive weaponry and bipedal carnivory, as well as for its sudden fall from planetary dominance about 65 million years ago. Dinosaurs have penetrated the public perception of prehistoric life so completely that the casual museum-goer is prone to indiscriminately identify any large, extinct reptile on exhibit as a dinosaur. The term “Dinosaur” refers to the members of a specific branch on the greater tree of reptile evolution – it is not a blanket descriptive term for anything extinct, gigantic and ostensibly reptilian. None of the early Mesozoic reptiles I mentioned in the opening paragraph are dinosaurs.

But what distinguished the earliest Dinosaurs from their non-Dinosaurian reptile contemporaries? Are modern-day crocodiles close relatives of dinosaurs? Answering these questions is not trivial and will require a fair amount of phylogenetic tree-climbing.

Step 1: Dinosaurs as Diapsids

Dinosaurs have two openings on each side of the skull behind the eye sockets. These holes, called temporal fenestrae, have margins that provide secure anchorage points for muscles involved in jaw function. The presence of these paired holes in the skull roof places dinosaurs within the group Diapsida. All living reptiles –with the possible exception of turtles and tortoises – are Diapsids by ancestry.

The skull of a primitive diapsid. Two holes, called temporal fenestrae, are situated behind each eye-orbit.

The Diapsida may be sectioned up into two distinct groups of reptiles:

– A group of reptiles that includes lizards and snakes in addition to a number of now-vanished creatures, such as the spectacular marine Mosasaurs. This group is formally called the “Lepidosauromorpha” and is of no further concern to us in this account of Dinosaur origins.

– A group that includes modern crocodillians, avian and non-avian dinosaurs, flying reptiles called pterosaurs and a bewildering assortment of lesser known extinct reptiles with varied body-plans, diets, native habitats and temporal ranges. These are the “Archosauromorpha“.

Step 2: Dinosaurs as Archosaurs

Archosaurs display a number of skeletal features that distinguish them from other reptiles:

– An opening in front of each eye-orbit called the “anorbital Fenestra”.

– An opening on each side of the jaw called the “Mandibular fenestra”

– Teeth that are “laterally compressed” – that is, flattened from side to side – and serrated.

– Teeth set in sockets

– A large protrusion on the femur, called the fourth trochanter, that serves as an attachment point for a set of thigh retracting muscles.

– A high narrow skull

– Various anatomical characteristics that indicate an upright or semi-upright limb posture, as opposed to the sprawling limb posture observed in modern lizards.

One of the main thrusts of my post is this: the earth was already inhabited by a wide variety of impressive, large terrestrial reptiles – most of them archosaurs or close relatives of archosaurs – when the first dinosaurs made their appearance on the evolutionary stage.

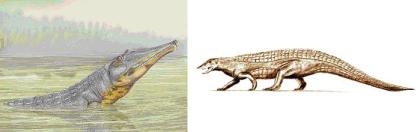

Phytosaurs were semi-aquatic, crocodile-like archosaurs from the early Mesozoic. They had elongate snouts and jaws rimmed with conical serrated teeth. Unlike modern-day crocodilians, they had nasal openings positioned high up on the skull – close to the eye-orbits in many cases – rather than at the tip of the snout. One can envision them snagging unsuspecting prey on the edges of rivers and lakes.

Aetosaurs were herbivorous archosaurs armored in heavy, interlocking dermal plates. It is tempting to think of them as prehistoric armadillos. Many were armed with fearsome spikes and stout claws. Rynchosaurs were strange plant-eating relatives of the archosaurs that had barrel-shaped bodies, stocky limbs and strong beaks that could cut through plant matter.

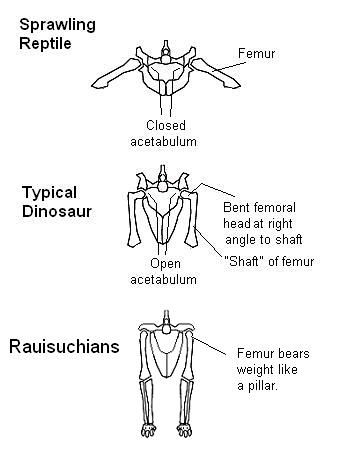

Before the ecological ascent of the theropoda (the dinosaur group that includes Tyrannosaurus rex, Velociraptor, and practically every other famous meat-eating dinosaur) the biggest land predators on the planet were Rauisuchians. They are generally understood to have been active, toothy, largely quadrupedal* archosaurs related to modern crocodiles. They were erect-walking animals with limbs oriented vertically below the body, rather than jutting out sideways – one of several traits they share in common with dinosaurs. The head of the femur fits into a downward-facing socket in the hip girdle called the acetabulum. The largest raiusuchians hit a length of over 7 meters, far bigger than the carnivorous dinosaurs of their time, and hunted large game.

Postosuchus kirkpatricki, a 4-5 meter long Rauisuchian

The first “true crocodiles” also appeared during the early Mesozoic. Modern-day crocodiles and alligators are built for a low-energy, semi-aquatic lifestyle. Crocodiles walk, for the most part, with a sprawling, lizard-like gait and spend hours basking on river-banks in a state of absolute intertia. Many early Crocodillians were, by contrast, slender-legged and fleet-footed terrestrial creatures. Some of them were even herbivores! Crocodile evolution is a fascinating story in its own right and will be dealt with more fully in a future post.

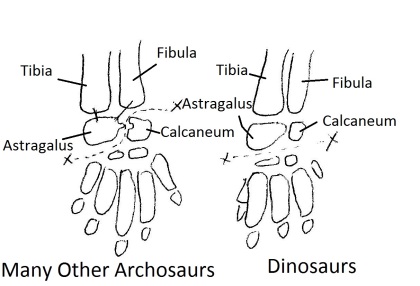

Step 3: Dinosaurs as erect-walking animals

Crocodillians, Raiusuchians, Aetosaurs and Phytosaurs can be readily distinguished from dinosaurs on the basis of their ankle morphology. In the former groups, the functional ankle joint is situated between two foot bones of similar size: the astragalus (an bone that forms part of the ankle; in these archosaurs it is sutured to the two bones of the lower leg, the fibula and tibia) and the calcaneum (heel bone). This configuration allows for considerable rotation of the foot during locomotion.

The ankle morphologies of Dinosaurs and other Archosaurs. The dotted line represents the position of the Ankle joint

In Dinosaurs, however, the articulation between the ankle bones is modified to produce a simple hinge joint. The functional ankle-joint is between the upper bones of the ankle (the calcaneum and astragalus) and the bones immediately distal to it (refer to diagram). The calcaneum was very small compared to the astragalus. The important implication of this anatomical design is that the foot was restricted to motion in a vertical plane. In other words, it could move back-and-forth but could not be twisted. This is a clear adaptation for upright, speedy running. A similarly structured ankle is also found in pterosaurs. Pterosaurs are aerially adapted reptiles and close relatives of dinosaurs.

Both the Raiusuchians and the Dinosaurs independently evolved an erect gait (where the limbs were positioned directly below the body rather than splayed outwards), but their anatomical approaches to this condition differed.

Three bones make up the pelvis: the pubis, the ischium and the illium. At the junction of these three bones, there is a socket into which the head of the femur fits called the acetabulum. In Dinosaurs, the head of the femur is bent – that is, offset at an angle to the main body of the bone. The head fits into the acetabulum. The dinosaur acetabulum, rather than being a solid pocket of bone, actually has an opening in it (an open acetabulum is one of the defining features of the dinosaur clade). The dinosaur femoral head is rather more barrel-shaped that the bulbous head of the human femur, limiting thigh motion to a plane parallel to the body.

Comparison of the primitive reptile, dinosaur and rauisuchian hip configurations. Adapted from skepticwiki’s article on dinosaurs.

The oldest known dinosaurs from the fossil record are lithe, bipedal carnivores like Staurikosaurus and Herrerasaurus. One of the interesting implications of this ancient bipedal body plan is that quadrupedal dinosaurs from later ages – horned Triceratops and mighty Brachiosaurus among them – belong to lineages that had to revert to walking on four legs from a state of two leged-ness at some point in their evolution.

Herrerasaurus, one of the earliest dinosaurs. Art by Nobu Tamura.

On the road to upright-walking bipedalism, the dinosaurs evolved a host of anatomical features that, taken in summation, set them apart from the rest of reptiledom. These include a distinct neck, a backward pointing shoulder joint, a hole in the center of the acetabulum, longer hind-limbs than forelimbs and long lower foot bones and digits.

Dinosaurs did not comprise a significant portion of terrestrial animal diversity for much of the early Mesozoic, but they eventually supplanted the raisuchians, aetosaurs, rynchosaurs and other reptile groups as the dominant vertebrates on land. Their spectacular success would last them through the middle and later Mesozoic – and beyond, given that birds are modern day descendants of dinosaurs.

But what made the ascent of the dinosaurs to ecological preeminence possible?

Some researchers have suggested that the upright-walking dinosaurs may have been more efficient terrestrial locomotors than their sprawling gaited and semi-sprawling gaited contemporaries – and that this was crucial to their long-term evolutionary success. Others have opined that the evolution of warm-blooded physiology in early dinosaurs may have given them a “competitive edge” over other reptile groups.

It seems likely, however, that the meteoric rise of this scrappy upstart clade had more to do with luck than any inherent superiority. After all, a number of other archosaurs evolved an erect gait but did not diversify to anywhere near the extent that the dinosaurs did, nor did they survive past the early Mesozoic. The fossil record suggests that two large-scale mass extinction events took place during the early Mesozoic, successively culling the landscape of various groups of large reptiles and transforming vegetation planet-wide. Early dinosaurs just happened to scrape through these tough times and inherited a world deserted of major competitors.

*There is evidence for at least facultative bipedalism in a number of raiusuchians.

Sources:

1. Lucas, Spencer G. Dinosaurs: the textbook. McGraw-Hill, 2004.

2. http://palaeos.com/vertebrates/archosauria/ornithodira.html (Accessed: 26 June 2012)

3. Fraser, N. I. C. H. O. L. A. S., and DOUGLAS HENDERSON. Dawn of the Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 2006.

Filed under: Uncategorized

“And suddenly marble turns into animals, dead things live anew, and lost worlds are unfolded before us.” – Balzac, in La Peau de chagrin

Note: A few terms may need some clarification. The Mesozoic era can be thought of as the “Age of Reptiles” – a span of time running from 250 to 65 million years ago, during which reptiles were the dominant terrestrial vertebrates. The Cretaceous period, which lasted from 145 to 65 million years ago, represents the final subdivision of this era.

In terms of gross energy yield, the simultaneous detonation of every atomic weapon on earth would be a puny sputter compared to the asteroid impact that brought an end to the reign of the dinosaurs. The collision event ejected massive quantities of debris and dust into the atmosphere, blotting out the sun. Ecosystems worldwide were subject to wild-fires, acid-rain, reduced plant/phytoplanktonic productivity and plummeting temperatures. Most of the large reptilian faunal groups that dominated the land and seas of the Cretaceous – non-avian dinosaurs, mosasaurs, pterosaurs and plesiosaurs – were wiped out forever.

The K/T extinction event: An asteroid collision brought an end to the age of the dinosaurs, 65 million years ago. Image credit to Don Davis, NASA

The K-T extinction event will be dealt with in more detail in a future post, but this section of finstofeet will focus on the brave, new Paleocene world that rose from the ashes of the Cretaceous. How did life on land recover after the dramatic demise of the dinosaurs?

Although the Paleocene forests were home to many strange and unfamiliar creatures (the remains of galloping crocodiles, shrews with trunks and kangaroo-like legs, hoofed predators and man-sized carnivorous birds have been unearthed from this period, along with other zoological oddities) they also bore the seeds of mammalian modernity: the Paleocene epoch saw the appearance of the earliest representatives of many present-day mammalian orders, including rodents, primates, ungulates and carnivorans.

What was the Paleocene? Did any modern mammal groups exist before the Paleocene?

The ‘Paleocene’ refers to the geological epoch that immediately followed the mass-extinction of the dinosaurs at the end of Cretaceous period. It lasted from 65.5 million years to 56 million years ago.

The first mammals of roughly modern aspect arose well before the end-Cretaceous extinction event, perhaps around 200 million years ago. Mammals in the age of reptiles were, as a rule, diminutive creatures – most of them were rodent-sized insectivores. A great majority were exceeded in size by even the smallest non-avian dinosaurs in their environment. A scant few attained dimensions comparable to the modern beaver or house cat. Repenomamus, the largest known mammal from this time period, was about a meter in length and is known to have preyed on small juvenile dinosaurs. There are examples of Mesozoic mammalian forms specialized for a semi-aquatic lifestyle, for ant-eating and even for gliding flight, but these are exceptional cases – most mammals of the age displayed rather unspecialized skulls, dentitions and skeletons.

Repenomamus, the largest known mammal from the Mesozoic, sating itself on a dinosaur hatchling. Art by Nobi Tamura.

For much of the Mesozoic, the mammals appear to have languished in a kind of evolutionary purgatory – restricted to a relatively small number of morphological types and ecological niches over an immense stretch of geological time. It is generally thought that the dinosaurs competitively excluded mammals from the medium-to-large predator and herbivore niches.

The Mesozoic Triumvirate

Three major groups of mammals carried over into the Paleocene from the Cretaceous period.

The placenta is a complicated mammalian tissue that serves as the interface between the maternal uterine wall and the developing fetus. It anchors the fetus to the uterus, supplies the growing embryo with oxygen and nutrients and eliminates the metabolic waste produced by it. It also acts as an important endocrine organ. Placenta-bearing mammals probably emerged around the middle of the Mesozoic and are represented today by over 5000 species, from elephants to humans to bats. These animals display a long gestation period and give birth to well- developed live young. Early placental mammals in the fossil record are recognized on the basis of certain shared features of the teeth, jaws, leg bones, foot bones and ankle joints (naturally, the presence or absence of a soft organ like the placenta cannot be used as a diagnostic tool when working with fossils).

The Marsupial clade also arose in the Mesozoic and managed to persist into the modern world – though its contribution to the present-day range of mammalian diversity is meager compared to that of placental mammals (there are a total of only 343 known marsupial species, mostly distributed in Australia and South America). Marsupials are popularly thought of as ‘pouched animals’ – in fact, the very name comes from the latin word for pouch, marsupium – but only 50% of living marsupial species actually possess a permanent pouch. Marsupials can more properly be distinguished from their placental counterparts on the basis of their reproductive cycle: Marsupials possess only a rudimentary placenta, with limited nutrient and oxygen exchanging capabilities. They have short gestation periods and give birth to tiny, incompletely developed young. The younglings are nursed on breast milk for an extended period of time (the lactation period far exceeds the gestation period). Subtle features of the upper and lower molars, in addition to the total number of molars in each jaw, also distinguish marsupials from placental mammals. Marsupials generally have lower metabolic rates, slower rates of postnatal growth and smaller brain dimensions than placentals of comparable size.

Adding to the mammalian diversity of the late cretaceous was a group of primitive, essentially rodent-like mammals called the Multituberculates. The clinical-sounding name refers to the fact that each cheek tooth in the jaws of these animals bore multiple rows of tiny cusps (bumps) or “tubercules” that operated against similar counter-rows in the opposite jaw. Like modern rodents, they bore a pair of enlarged shearing incisors at the front of each jaw. In terms of geological longevity, it could be argued that they were the most successful mammalian order of all time, lasting for a span of over 120 million years. Marsupials and Placental mammals are much more closely related to one another than either is to the Multituberculates. Judging from the structure of the pelvis, it seems very likely that Multituberculates gave birth to immature, live young rather than laying eggs like their reptillian forebears. Unlike the marsupials and placental mammals of the Mesozoic, the Multituberculates left behind no living descendants.

It is worth mentioning here that a group of primitive egg-laying mammals, the monotremes, also made it into the Paleocene. They are represented today by just one species of Platypus and four species of Echidna.

The sudden disappearance of the dinosaurs opened up a plethora of new niches for the mammals to radiate into. The world was warmer and wetter in the Paleocene than it is today, with rainforests ranging over most of the continents. The continents themselves, while not entirely alien in shape and extent, occupied markedly different longitudinal and latitudinal positions in the Paleocene than they do today. A map of the world at that time is included below.

A Paleocene World Map

So we’ve set the stage. What sorts of mammals could we paint into a Paleocene landscape?

The marsupials appear to have undergone a significant reduction in diversity at the Cretaceous-Paleocene boundary – only one genus, Peradectes, is known to have made it across successfully. The placentals and multituberculates sustained fewer casualties by comparison.

The explosive diversification of mammalian morphotypes to fill ecosystems effectively emptied of large vertebrates did not begin immediately after the fall of the dinosaurs. For example, it was only towards the end of the Paleocene epoch that the first truly large-bodied mammal herbivores and carnivores began to arrive on the scene. Agusti and Anton’ (2002) go so far as to describe much of the Paleocene as being “an impoverished extension of the late Cretaceous world”. Any overview description of the mammals of this period is destined to devolve into a tiresome catalogue of strange names and anatomical characters. I have tried my level best to supplement my writings with pictures to help you visualize the animals I describe below.

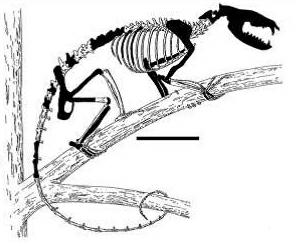

The Multituberculates (hereafter shortened to ‘multis’) reached the peak of their evolutionary fortunes during the Paleocene. The Ptilodonts can be regarded as typical Multis – they had large, rodent-like incisors perched at the front of each jaw, separated from the cheek-teeth by a toothless space. They had elongated blade-like lower premolars, designed for cracking nuts and hard seeds. Like most Multis, the Ptilodonts appear to have been largely herbivorous, perhaps supplementing their diet with the occasional invertebrate. Ptilodonts had grasping claws, a prehensile tail, large toes and feet with a wide range of motion. These traits indicate a heavily arboreal lifestyle. In summary, the Ptilodonts were squirrel-like animals, both ecologically and morphologically.

Left: The rodent-like skull of a Ptilodont (by Nobi Tamura), Right: The beaver-sized Taenolabis (by Bruce Horsfall)

The largest known multi approximated the size of a beaver – the short-snouted, heavily built Taenolabis. It had large grinding molars and was clearly a ground-dwelling herbivore. The Multis ultimately bought the farm about 30 million years ago – succumbing, perhaps, to stiff competition from true rodents, primates and herbivorous ungulates.

The transition into the Paleocene was turbulent for the Marsupials and they never truly recovered their former level of diversity in the Northern Hemisphere. The southern continents, however, were a different story. Marsupials formed a sizeable chunk of the mammalian fauna in Paleocene South America (up to 50%). A number of these Marsupials can be characterized as belonging to the same taxonomical order as modern opossums. Some of these were adapted for burrowing, others for scaling trees. Interestingly, marsupial equivalents of rodents and carnivorans also evolved in South America during the later phases of the Paleocene. The weasel-sized arboreally-proficient marsupial Mayulestes probably sought out frogs and small mammals as prey; It was similar, in many ways, to the marten.

Placental mammals, piddling contributors to the range of mammal diversity for most of the Mesozoic, managed to outshine both the Multituberculates and the Marsupials during the Paleocene. We shall consider several unique and interesting placental animal groups that lived in the Paleocene in the following passages.

The Lepictids – It is tempting to observe the tiny sizes, small brain-cases, pointed snouts and insectivorous diet of hedgehogs, shrews, golden moles, elephant shrews, treeshrews, tenrecs and moles and conclude that they all belong to a single taxonomic category of mammals. This is not really the case, and molecular analyses – as well as studies in comparative anatomy – demonstrate that these 7 animals represent up to five different mammalian orders: Erinaceomorpha (hedgehogs), Soricomorpha (shrews and moles), Macroscelidea (elephant shrews), Scandentia (treeshrews) and Afrosoricida (tenrecs and golden moles).

The tree-tops and underbrush of the Paleocene were home to a great many such small-to-medium sized insectivorous creatures, representing different genera, families, orders, superorders, infraclasses and subclasses – a number of these (in South America, at least) were marsupials, others were Multituberculates and some were early members of the currently existing placental orders listed in the previous paragraph. Still others belonged to placental families and orders that kicked the bucket by the end of the Paleocene: the long-legged lepictids, the shrew-like paleoryctids or the semi-aquatic, fish-eating, otter-like pantolestids, for example. One of the most charismatic placental mammals recovered from the Paleocene is lepictidum – a sort of strange cross between an elephant-shrew and a kangaroo. It was about 60 to 90 centimeters long, had lengthy hind-limbs, shortened fore-limbs and a slender snout that sported a short trunk. Like many other mammalian insectivores, the skull was quite unspecialized. It is unclear whether this animal ran on all fours or hopped like a wallaby. And yes, as fossil genera go, Lepictidum is unbelievably cute. The video below represents one animator’s impressive attempt at bringing this animal back to life.

Plesiadapiforms – We can tease out the beginnings of our own order, Primata, from amidst this Paleocene profusion of tree-climbing and insect-munching forms. Modern Primates share a number of features: among them, a short muzzle, forwardly directed eyes with stereoscopic vision, hands with nails rather than claws and cheek teeth with rounded cusps. Most Plesiadapiformes display none of these characters, possessing a long snout, strong, curved claws and side-facing orbits for the eyes. They can, however, be related to primitive tarsier-like primates mostly on the basis of shared features of the teeth and the auditory bulla, a bony structure that encloses the bones of the middle ear. It is likely that they were close relatives of true primates, if not directly ancestral to them. They were extremely abundant in the Paleocene and are interpreted as being lemur-like in appearance. They had long digits and flexible limbs for maneuvering through the forest canopy. Over 25 genera and 75 species of Plesiadapiformes have been discovered from this period – leaping about the tree cover as far north of the tropics as northern Wyoming, which was warmer and less arid during the Paleocene.

Condylarths – Primitive ungulates, called Condylarths, also existed in the Paleocene. Many of them bear little semblance to modern hoofed animals like horses or deer. For example, Arctocyon was a wolf-sized condylarth with the limb proportions of a bear and a diet that included meat. It had a pair of impressive lower canines and a long, robust skull. Its cheek teeth indicate that it was primarily a plant-eater. It is identified as a primitive ungulate by subtle features of its limb joints and dentition. Dissacus was another example of a condylarth that consumed meat. It had digits that terminated in hoof-like structures. Many different groups of condylarths have been recognized in the fossil record.

Some of the Condylarths were browsers like Ectoconus or Phenacodus, and possessed clear signs of tapir-like hooves. Some of these animals were well-adaptated for running. The condylarths are generally regarded as being the basal ancestral stock from which the odd and even toed ungulates arose.

Titanoides, a late Paleocene herbivore. By Smokeybjb

By the end of the Paleocene, various large bulky herbivores appeared on the scene – some of them Condylarthian in origin and others not. Titanoides was a strange non-condylarthian herbivore that approached the size of a Rhinoceros and had giant saber-like canines and long forelimbs. The earliest civet-like ancestors of dogs, cats, hyenas and bears also evolved in the Late Paleocene – though their story will be told in another section of finstofeet. It is astonishing how many wildly different lineages – ptilodonts, marsupials and plesiadapiformes, among others – evolved chisel-like incisors and rodent-like skulls during this epoch. True rodents arrived onto the scene at the end of it all, competing with and ultimately eclipsing the various pseudo-rodents of the Paleocene.

Were there any large non-mammalian predators during the Paleocene?

One of the most unusual aspects of the Paleocene was the presence of large predatory birds and reptiles that occupied the topmost rungs of the food-chain in terrestrial ecosystems across the world.

The K/T extinction event did not put the dinosaurs out of business entirely; they were survived in the succeeding age by birds (some aspects of the dinosaur-to-bird transition have already been dealt with in the ‘Taking Wing’ series). Fossil evidence suggests that birds weathered the Cretaceous-Paleocene transition poorly, with only a few taxa escaping extinction. These surviving forms eventually gave rise to all the different families of birds that we currently observe.

There is molecular data that contradicts this picture, pointing to a pre-K/T event divergence for many of today’s major bird lineages.

Gastornis, the ‘terror bird’

In any case, by the late Paleocene, one group of birds had lost the ability to fly and assumed the form – in likeness of some of their extinct theropod relatives – of large, land-bound, predaceous bipeds: the Gastornithidae. These “terror birds” were up to 2 metres tall and small, non-functional wings. They had large, powerful beaks for capturing and tearing prey apart. It is often depicted as feeding on carrion and mammals. They are related to modern waterfowls.

Update/Correction (January 2013): Some recent evidence seems to suggest that the Gastornithidae were actually herbivores!

Pristichampsus, a cursorial crocodile. Illustration by Robert Bakker

Crocodillians and crocodile-like Champsosaurs flourished during the Paleocene. Pristichampsus was a land-walking 3-meter long crocodile from this period that had hoof-like toes and long legs. It was heavily armored and capable of ‘galloping’ after fleeing prey. Archaic marine crocodiles roamed the seas, while a variety of crocodiles, alligators and now-extinct champsosaurs inhabited swamps and marshes the world over – relicts of a by-gone age of reptiles. Just recently, specimens of a monstrous 40 to 50 foot snake, appropriately named Titanoboa, were uncovered from this period. It was, by far, the longest and heaviest snake known to science. I’ll leave you with this rather entertaining teaser for the Smithsonian Channel’s special on Titanoboa

NOTE: Title card art by Nobi Tamura

Sources:

1. Agustí, Jordi, and Mauricio Antón. Mammoths, sabertooths, and hominids: 65 million years of mammalian evolution in Europe. Columbia University Press, 2010.

2. Prothero, Donald R. After the dinosaurs: the age of mammals. Indiana University Press, 2006.

3. http://www.paleocene-mammals.de/ Accessed: 23 May 2013

Filed under: Uncategorized

The force of gravity – together with certain physiological and ecological constraints – holds in check the evolution of ever larger body-sizes among mammals on land. By becoming secondarily adapted to life in water, however, whales have been able to circumvent at least some of these size restrictions.

Left – A Blue Whale, the largest living animal known to science, Right – The African Elephant, the largest extant land animal

The largest extant land mammal – the African Elephant – is considerably outweighed by sea-going baleen whales of even middling proportions. In all of the Cenozoic era (the 65 million year period following the extinction of the dinosaurs), no terrestrial mammal ever grew to match the modern Gray Whale, let alone the Blue whale, in body dimensions. The reduced weight constraints of an aquatic medium accounts for this apparent difference in maximum attainable size.

Outside of the mammals, however, there is one group of extinct land creatures that did approach, and in some cases surpass, the awe-inspiring lengths of the largest baleen whales* pushing the evolutionary envelope in terms of height, length, weight and girth in a way that no other terrestrial animal group ever did.

Together with whales, the sauropods are examples of animal gigantism par excellence.

What are Sauropods?

The term “Sauropoda” refers to group of quadrupedal, megaherbivorous dinosaurs that existed for a span of over 135 million years – from the close of the Triassic period to the very end of the reign of the dinosaurs. Their highly distinctive body plan was characterized by:

1) An elongate neck. One that, in some genera, grew to double the length of the trunk.

2) A small skull relative to body size, with enlarged eye-orbits and highly placed nasal openings

3) A massive body with a long tail